Myth buster - Some LinkedIn stuff

Busting some LinkedIn stuff: a selection of posts ... hopefully you don't make it there

Welcome to the second of edition of Mythbusters, the special issues, separated from the chapters of The systematic venture.

In the 2020s, entrepreneurship is fundamentally a social matter, significantly influenced by social media. This trend mirrors how dating and friendships have evolved, where people often pursue activities more for social status than for genuine interest.

Possessing an audience in this era is a superpower, offering a powerful lever for securing deals, investing, creating companies, and potentially attaining wealth and fame. Indeed, a large, engaged audience can sometimes outweigh the ability to create outstanding products.

However, this comes with a major pitfall. Once someone has an audience, or feels the need to maintain or create one, there's a strong temptation to continually engage, often speaking out without being fully prepared or informed.

In essence, many content creators frequently post dead-wrong assertions simply to maintain their online presence, and their followers often praise these posts merely because of the creators' large audience.

I like calling the Greenspan effect, named after former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan, who famously misjudged the 2008 financial crisis. Just as Greenspan's erroneous predictions about the crisis were taken at face value due to his status and reputation, so too are the posts of some high profiles often unquestioningly praised by their followers.

This issue is particularly prevalent in the startup world, where a LinkedIn presence sometimes replace the need for actual work, at least before customers and investors figure out it´s all talk.

In today's discussion, I will address and debunk several LinkedIn assertions from last week that seem fundamentally flawed to me, yet have, for some reason, received considerable acclaim.

Myth #1 - Software multiples are cheap

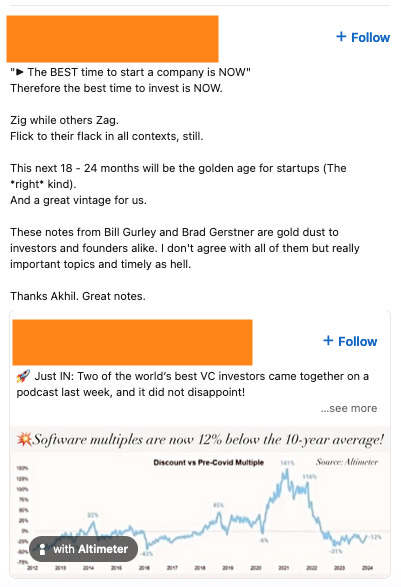

Here is a post from a startup advisor, reposted by a VC partner, arguing that because software multiples are back to pre-COVID levels, it's the best time to invest. Software multiples are 12% below the 12-year average, suggesting they are cheap and it’s a good time to invest.

Now, let's examine the reaction of a VC, which seems absolutely dreadful to me. Let's dissect it and debunk the generally admitted truths in this post, which just aren't so.

Basic statistics

Most people struggle with basic statistics.

Some investors, startup advisors, and even traders just don’t understand how averages work. Let's take an example: consider a concert hall with 9999 people, each earning $100k yearly. The average wage in the hall is $100k.

Now, imagine Jeff Bezos attends this concert. Last year, Jeff Bezos made approximately $70 billion. Suddenly, the average wage in the stadium skyrockets to $7,099,990. But this doesn't mean the crowd is wealthier; it's just one person with an astronomical income among them.

Many investors and corporate advisors lack a basic grasp of statistics. If you look at the post-COVID era, where the world saw record-breaking leverage and price-to-earnings valuations, then of course, current software multiples appear cheap.

The same way an individual in the concert seems extremely poor compared to the average, once Jeff Bezos shows up.

But if you understand the basics of interest rates and consider a longer period than just the past ten years, which saw record lows post-2008 crisis, then you'll see that software multiples are still grossly overvalued.

Time to invest, time to start a company

And here comes a VC, fooled by the ten-year curve, reaching an even more erroneous conclusion: the best times to start a company are the best times to invest.

Fuck no

The worst times to invest are actually the best times to start a company, because 98% of businesses will never raise a dime from VCs too focused on a terribly narrow niche of businesses and founders. The last decade was amazing for VCs, filled with free LP money as savings and low interest rates would just ruin incentives to go into less risky investments.

On the contrary, it was for the other 98% an incredibly hard time to create companies, as the competition with VC-backed companies offering absurd wages and unsustainable subsidized growth methods completely distorted a lot of markets.

As a bootstrap entrepreneur, I love it when the VC market slows down, and the last year has been the absolute best by far. So many of these bloated, funded companies are just deadlocked with tentacular teams, very high costs, and just cannot operate anymore.

Myth #2 - I don’t even know where to start

I know a lot of the readers speak spanish, for those who dont, it’s a post on why Rappi became a unicorn. It appeared on my feed somehow. Nothing personal, I’m happy to debate, but I just think he is wrong on … well pretty much everything in this post.

And yet, it generated large praise, let’s dig in, point by points.

Network effect...

And here comes the first buzzword: network effect. I think it's the most overused, least understood marketing and growth term. Network effect in marketing applies when:

A company's product value grows exponentially as the number of people using it increases. Why? Because the number of two-node connections in a network with n elements is n squared.

Consequently: the users of your product must interact with each other, or at least have the ability to do so.

Rappi has aggressive acquisition, but no true network effect. It was an aggressive discount-based strategy to bring restaurants onto the platform, hook them with exclusivity, and then attract customers: yet more people don't make it exponentially more interesting as you don’t interact with other Rappi users. This is total nonsense.

Yes, more restaurants make it more attractive, but it's not a PayPal or an Instagram use case here.

Fast scaling

I mean... this is true, but it's precisely what makes them terribly fragile now. Quick scaling is not what makes them a unicorn; it's actually pretty much the contrary: dumb money infusion at absurd valuations allowed them to deploy massively and reach unicorn status.

In most cases, unicorns scale with decreasing marginal revenue, which means they lose more money as they grow. Scaling and profits are two different beasts … hard to reconcile.

Frequent new use-cases

And again, a horrible take.

Rappi destroyed itself by multiplying useless use-cases that became digital zombies on the application. To this day, as the company is giant, they have no clear direction on what is actually the focus at the regional level: are they a consumer bank, a food delivery app, or both? What is their priority?

The myriad of use-cases available on Rappi app probably didn't do much good for their growth and their revenues. In fact, they have a power-law distribution of revenue, where 90% of the income stream comes from 5% of the offerings.

The worst take : User activation, and competition is for losers

What the actual hell? Rappi is facing financial issues and lack of profitability because they competed on price, and subsidized their growh to gain market shares in food delivery.

This is like, totally the contrary. Rappi brings no special innovation, but they infused their growth with money and an army of salespeople to bring in restaurants, and then users. The harsh competition – because they have no exclusive product that doesn't exist elsewhere – is the very reason they needed so much money and can’t have monopolistic returns.

Well, non-profitable companies reaching unicorn status exist because some nut-heads at VC funds think they're future world giants... and sometimes, it happens.

Love,

Voss